My high school classmates and I are fast approaching a reunion. I’m looking forward to it, to reconnecting, swapping life stories, sharing pictures from then and now. Predictably, many of us knew each other through chunks of our formative years. We spoke of aspirational dreams through our blooming hormones and formed many of our values with, on and through each other. We shared our innocence before the world moved us into its harsher realities. A crew on the reunion committee asked that we each pull together some remembrances in order to share them. I’ve read the submissions thus far and oh my, the floods of memories they have stirred. Here is some of what came up in those waters for me.

My dad’s career as an engineer with Union Carbide moved my family to Tokyo from Greenwich Ct., in 1960. Carbide had just initiated a joint venture with Nippon Unicar, so off we went. My folks, Ray and Marshie, were thrilled to return…they’d been there under General MacArthur during the occupation days, with part of that rebuilding effort. Dad, had partnered with the brilliant Seymour Janow, travelling the length and breadth of Japan, assessing and where possible turning munitions factories back into fertilizer plants for a starving nation. Mother, partnering with dear pal Mrs. Connor and under the directive of Mrs. MacArthur, launched their school, Western Customs and Manners, open to all wives of Japanese military officers.

We lived for the first many years in a rambling, quasi Western, great old house rented by Carbide. There were expansive gardens, well tended to by the property’s long-term gardener. He was of an age that meant he had survived WWII in Tokyo which meant in turn that the emotional wounds inflicted by that war must still have been in the healing process. Mom was West Virginia born and some healthy percentage of her joy came from keeping her hands in the dirt, digging, planting, watching things grow. This meant that, however reluctantly, the gardener had to deal with this American, this force who was my Mother, in “his” garden. He was cordial but remained distant and about his work.

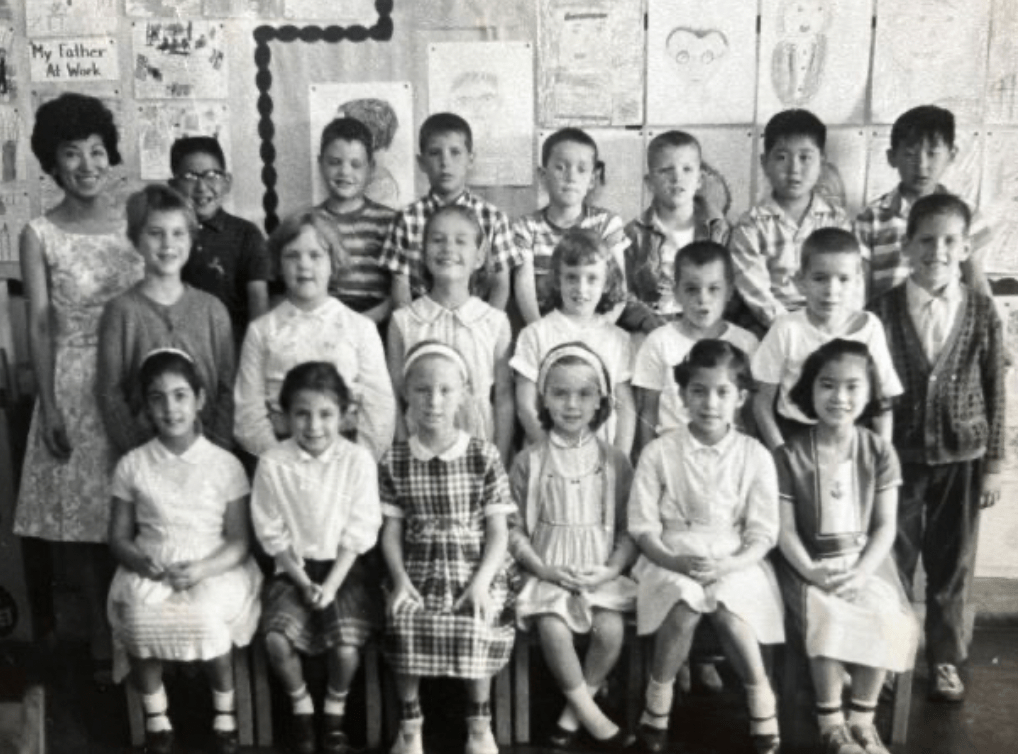

My sister Mara and I rode bikes throughout the neighborhood from as young an age as I can recall with total freedom. Oh sure, the kids our age on the streets would point, laugh and call us “gaijin” (literally translates as barbarian) but the taunts were more in astonishment to our novelty than malice and we peddled on, carefree. We were regulars at the candy shop, wanted to be just like the beautiful butcher’s wife Yaeko-san when we grew up and had little girl crushes on the handsome tofu shop owner. This was our world and we were happy in it. Long term US Cultural Attaché, Walter Nichols soon became a key figure in our lives. He was instrumental in bringing to Japan a host of American artists, many of whom, happily for us, ended up staying in our home, some for extended periods of time. Henry Mancini, Tennessee Williams, Harold Clurman to list but a starry few. Mara and I took these extraordinary experiences for granted. Now we know how incredibly privileged we were and are unspeakably grateful for it all. Vivid memories from ASIJ (American School in Japan and later from Sacred Heart) linger…Mrs. Sato in first grade, Miss Kochi in 2nd, Mrs. Story in 6th, Dr. Cleveland who ran the swimming team. To this day I put both hands on the edge of the pool at the end of a frog lap lest I, again, incur his wrath. Saturdays were spent at the American Club. Ever smiling Ken-san at the front desk would check us in. Ballet or bowling class…pizza and root beer followed by the matinee movie. I’m still traumatized from the day at age 6 I realized, after swimming and whilst changing into my sundress, that I’d forgotten to bring underpants to wear for my upcoming bowling class. A wet bathing suit bottom had to suffice. Oh, the horror!

We spent idyllic summers in a then faraway and tiny, rustic village, Gotemba near the base of Mt. Fuji. It was then a three plus hour drive curling up winding two lane hilly passes. Dishearteningly, when I took a drive outside Tokyo in recent years, we passed the Gotemba turn off on a spit and polish four lane highway in a mere forty-five minutes. To add insult to injury, there was a Starbucks prominently advertised at the exit. We motored on. Back in the day the village was just that…tiny and dotted with thatched roofed wooden houses on dirt paths that variously doubled as the rice, butcher and vegetable shops. Our house itself, well more cabin really…ok…shack…had been the countryside get away for the retired missionary who had apparently taught Hirohito, English. She could live there through the war, safe from bombs. There’s a story. Everything creaked, we’d burn the wood to heat water and we loved it. Days were spent formatively out of doors playing endlessly in the woods and exploring favorite abandoned and over grown Shinto shrines. We imagined, even hoped, that they were haunted.

As we had no grandparents on deck in faraway Japan, my folks saw to it that we, and they, were not without elders. What a gorgeous cast of characters they assembled. George Furness. Harvard man, always dapper who had been a key lawyer during the war crimes trials and later went on to be one of the first foreigners, perhaps the first, to pass the Japanese law bar. He married a gorgeous woman there and their daughter, a contemporary of mine, has been a life long pal. Then there was Bryn Mawr educated Chiye who had, before the war, married Marchioness Hachisuka. Because she was bicultural, bilingual and a royal, she was deemed the ideal private, and secret, go between for Hirohito and MacArthur. She would ferry back and forth across the way from US Occupation Headquarters building on one side of the moat to the Imperial Palace on the other side with proposal details of how Japan was to move forward…infrastructure, government, trade, etc. Red lacquer nails, a chignon and smart suit for one. No makeup and a shibui kimono for the other. It was Chiye who dissuaded MacArthur from deposing the Emperor, explaining that the General could take away all other titles, hers included, but to depose the Emperor would be to ravage the soul of the Japanese.

There was Queenie Day and her husband James Mason. Entrepreneurial businessman James, was (if the tale told me was correct) the son of a 19th century British missionary and Japanese wife. When he’d been sent to university in faraway England, he clapped eyes on Queenie, she on him and that was that. One year after he had returned to Japan in 1908, Queenie to the horrified dismay of her parents, set sail to Yokohama and there on the dock married her true love. They had lived through the great Kanto Plains earthquake and subsequent tsunami of 1923, through the depression of the 1930’s and through both World Wars. Life was good when I knew them. They had survived so much and lived to see a blossoming Japan.

There was artist Frances Blakemore and her attorney husband Tom. Frances, a generation younger than James, also had been raised in pre-war Japan the child of missionaries. When the rumblings of war had begun, her family had moved to the America where, although a citizen, Frances was a fish out of water. At 18, the US government conscripted her to help break the code. On more than one occasion she had struggled, she said, with handing over a cracked code, knowing that to do so was to sentence many in the country of her heart, to death. She justified the reveal however, thinking that surely these actions would hasten the end of war. As soon as the war was over she moved back to Tokyo and set up a hugely successful art gallery in the famed Okura Hotel and serially launched the successful careers of young, burgeoning Japanese artists. She and Tom kept a small farmhouse property not far outside Tokyo that we visited once. In it they housed their considerable collection of items of invention, indigenous to pre 21st century Japan. Farm implements and the like. Flourishing in the front yard were rows of miniature fruit trees cultivated by contemporary Japanese scientists for low water consumption and high yield. When in the Blakemore’s dotage they moved to Seattle, the farm was given to the Japanese government. Penance? Whose to say.

We also had adoptive aunties and uncles. Notably Asia hands Bill and Jan Anderson. Bill had survived four years in a cage as a Japanese prisoner of war and was now at the helm of NCR in Tokyo. We traded dogs and sleep overs with their daughters, with whom we now enjoy a third generation of friendship between our own children. There were the Kogans, who had escaped pogroms in Russia, then Shanghai and were now prominent business people in the safety of Japan. The Tarnas, entrepreneurial pearl merchants. Lanky, Don Gregg an affable if lowly (or so we thought) State Department employee, who turned out to have been the CIA Station Chief through much of the Vietnam and Cold Wars. There were legendary journalists, John Roderick (AP) and John Rich (NBC). Roderick had in the mid 1940’s, lived in the caves with leaders of the Chinese Communist rebel movement. Those had included Mao and Zhou Enlai, among others. Rich had traveled with Hirohito and covered Shanghai’s fall to the communists.

Collectively, those listed and beyond made up an extraordinary extended family. Multi national, pioneering parents of every conceivable faith and talent who proactively built cross cultural bridges. Moms who figured out how to raise their kids in what for them must have been a very, very far away land. We there, became each other’s extended family and so it remains. Lifelong friends from then are one of the many life treasures I cherish. Occurs to me that we each were ushered into a global reality long before such a term became popular. Lucky, lucky us.

As an adult I’ve made my way as a journeyman actress on tv and stage. All that began during my growing up years in Tokyo when Toho, a large entertainment concern based in Tokyo, kindly took me under their wing. To my knowledge I was the first gaijin to train at their Geino Academy, perhaps the only? Gosh, maybe they found the experience so distasteful they never permitted it again! I worked a few times in productions at Toho’s Imperial Theatre in both English and Japanese (which had been easy to learn at so young an age.) Like many of us, I “taught” English on one of the NHK language programs now and then. I eventually did some pop recordings too which I suppose are what gave me the appetite for concerts and recordings I get to do now.

I want to circle back to the gardener and Mom. Five years into our residency and shortly before the gardener was to retire, Mom came out to the garden one day to discover him midst digging a deep hole. Rather than risk breaching their tenuous trust, she did not ask his intentions, but took instead to trimming azaleas. One hole advanced to a total of five at which point he called her over to peer into the pits at what looked to be stone boulders. Boulders she would learn that he had buried for protection when the bombs had started to fall. Enlisting some neighborhood help, he was able to pull them up from their protective graves and stack them so as to be reassembled back into an ishitoro, or stone lantern. It was beautiful and once again a vessel of light, only now in more ways than one. When we very eventually moved from that home our landlord bequeathed the ishitoro to Mother. Could the gardener have imagined over those terrifying hours when he buried the ishitoro, that there would come such a day? Ofcourse I will never know but I would like to think that the gardener would have approved this extraordinary act of kindness on the well worn bridge of cross cultural ties.